The data set comprises of cross-sectional long series of credit to non-financial sector constructed collectively by the BIS and its member central banks; and perhaps more than 50% of this data set dates back way before 1990. Importantly, the data set provides a good breakdown by (1) borrowers (whether lending is to households or to corporations), and (2) lenders (whether lending was provided by domestic banks or other sources, i.e. domestic nonbanks and cross-border lending). I originally only wanted to see to what extent The Fragile Five (Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey) is relying on non-traditional funding (i.e. funding not by domestic banks), though some compare-and-contrast surprisingly gives us a little peek inside shadow banking in China.

1 - What is Shadow Banking?

In a nutshell, shadow banking simply refers to non-bank institutions (e.g. private firms, investment banks, money market funds, securitization companies, etc.) whose activities essentially carry out the functions of a traditional commercial bank (i.e. creating liquidity via its own borrowing/lending). These institutions have been around for long, though they only caught attention after the 2008-2009 financial crisis, since many economists believe that it was the uncontrolled and unregulated activities of these institutions that generated great maturity mismatch and high leveraging, setting up the stage for the crisis.

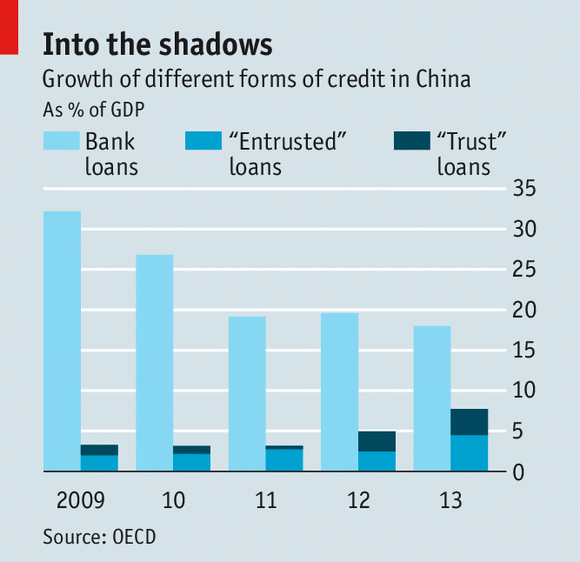

Previously, researchers only focused on the shadow banking sector in advanced economies. Nonetheless, the spotlight is now shifting gradually to the emerging markets (EMs), as there have been evidences which point to a growing shadow banking system in these economies. For example, the Economist had an article about how companies are starting to lend to each other and earn profit, just like banks, in China. Borrowing the article's chart, we could see that other (non-bank) forms of lending are growing more and more rapidly, while the growth of traditional bank's lending (light blue bar) is slowing down.

|

| Source: The Economist |

2 - In what EMs is shadow banking significant?

So this is a little visualization I made from the BIS data set mentioned above:

|

| Fraction of Lending to Private Non-financial Sector in Emerging Markets provided by Banks (green) and Non-banks/Cross-border Lending (Blue) Source: BIS, own calculations. |

The countries represented in the six charts are (from left to right, top to bottom) Brazil, China, Indonesia, India, Turkey, and South Africa. There are good and bad news. The good news is that all the Fragile Five countries (everyone except China (top-center), and maybe Turkey (bottom-center)) has a very solid domestic banking system which provides most of the credit to its non-financial sector. This has a very great implication: if capital flows is reversed (say, in a year or two), the direct impact on the real (which is non-financial) side of the economy will be relatively small. Let's not be all optimistic, however, since the domestic banks themselves have their own risks from borrowing abroad and from non-traditional sources; so the indirect impacts will still be there. Though, I must say, the levels of lending provided by domestic banks as above are still very impressive in my opinions.

Now we turn our attention to China, the only country among the six above that we can actually see a sizable blue area, which appeared at around 2005, and is gradually growing. In other words, Chinese households and private non-financial firms are getting funding from domestic non-banks and foreign sources. The BIS data set indicates that this funding gap amounts to 26261 billion yuan in December 2013, or around 4.25 trillion USD by today's exchange rate. Remember that this funding gap can come from two sources: (1) domestic non-banks (shadow banks) and (2) foreign lending. I made a quick search, and Chinese's state newspaper Xinhua reported that Chinese's foreign debt is approaching 1 trillion USD in early 2014. If we are to trust this source, that leaves us with roughly 3.25 trillion USD of shadow banks' funding! That's almost twice the US foreign debt, and accounts for 19% of total lending to private non-financial sector in China.

Why do we care?

Of course I personally find it very scary that 1/5 of lending to households and corporations in China comes from shadow banking. This sector provides what seems to be attractive funding during boom time, only to create serious liquidity problem during crisis period. Of course, the question of "to what extent does shadow banking impair the economy" requires formal modelling; though, for demonstration, if 50% of shadow banking funding in China dries up during crisis, that jeopardizes 10% funding to private households and nonbanks, i.e. real consumption and real production. I guess after the US-led crisis in 2008, it may still be too soon for another crisis at the world's biggest exporter and biggest lender.

Scary, isn't it?